Book Project

The Promise and Peril of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

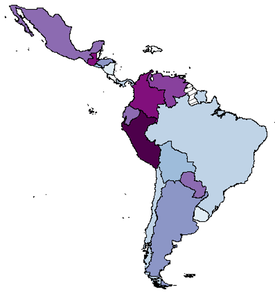

Members of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Shading illustrates variation in the number of compliance orders received from the Court; darker shades indicate more compliance orders.

Members of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Shading illustrates variation in the number of compliance orders received from the Court; darker shades indicate more compliance orders.

My book project is about the Inter-American Court of Human Right's dual roles as enforcer and creator of human rights in Latin America and the increasing tension between them. Through its role as enforcer, the Inter-American Court focuses on improving states' current human rights practices and remedying past abuses. As creator, the Court is more aspirational, setting standards for human rights that may not be achievable yet, but are desirable. However, these roles may conflict when the Court's aspirational goals lead it to advance human rights norms past the point of what is currently enforceable within the societies it serves.

The first half of the book, which is based on my dissertation, focuses on the fixed and circumstantial challenges to compliance. By fixed challenges, I mean the background and institutional conditions of the Court's existence --- the kinds of states that joined and when; institutional rules that dictate what kinds of cases move forward --- that are largely outside of the Court's control. These managerial challenges limit states' capacity to comply in important ways. I then turn to the circumstantial challenges, or those that reflect the current political conditions in which the Court operates. I show that in some of its most consequential rulings, the Court functions as an anti-majoritarian institution, ordering remedies for human rights violations that citizens do not necessarily want. In particular, I show that in cases implicating the military, the domestic leader's probability of compliance varies depending on public attitudes toward the military, as well as the extent to which those opinions need be taken into account. [Poster presenting survey evidence of attitudes on compliance - PolMeth 2024]

The second half of the book focuses on the Court's aspirational role as creator of new norms in three areas. First, the Inter-American Court has advanced jurisprudence on restitutio in integrum for human rights violations, or what it truly means to make a victim of a human rights violation whole. Second, the Court has adopted expansive rules on state responsibility that allow for attribution of crimes that began prior to the state's acceptance of the Court's jurisdiction and, in some cases, for crimes that were actually committed by non-state actors. Finally, the Court's opposition to amnesty laws has prompted a variety of domestic responses, including at least one instance in which a state overturned its amnesty law on the basis of the Court's ruling against an entirely different state (which, coincidently, has yet to overturn its own law). This illustrates how even in instances of non-compliance, the Court's rulings may still effect change.

The first half of the book, which is based on my dissertation, focuses on the fixed and circumstantial challenges to compliance. By fixed challenges, I mean the background and institutional conditions of the Court's existence --- the kinds of states that joined and when; institutional rules that dictate what kinds of cases move forward --- that are largely outside of the Court's control. These managerial challenges limit states' capacity to comply in important ways. I then turn to the circumstantial challenges, or those that reflect the current political conditions in which the Court operates. I show that in some of its most consequential rulings, the Court functions as an anti-majoritarian institution, ordering remedies for human rights violations that citizens do not necessarily want. In particular, I show that in cases implicating the military, the domestic leader's probability of compliance varies depending on public attitudes toward the military, as well as the extent to which those opinions need be taken into account. [Poster presenting survey evidence of attitudes on compliance - PolMeth 2024]

The second half of the book focuses on the Court's aspirational role as creator of new norms in three areas. First, the Inter-American Court has advanced jurisprudence on restitutio in integrum for human rights violations, or what it truly means to make a victim of a human rights violation whole. Second, the Court has adopted expansive rules on state responsibility that allow for attribution of crimes that began prior to the state's acceptance of the Court's jurisdiction and, in some cases, for crimes that were actually committed by non-state actors. Finally, the Court's opposition to amnesty laws has prompted a variety of domestic responses, including at least one instance in which a state overturned its amnesty law on the basis of the Court's ruling against an entirely different state (which, coincidently, has yet to overturn its own law). This illustrates how even in instances of non-compliance, the Court's rulings may still effect change.

Publications

Johns, Leslie and Francesca Parente. 2024. "The Politics of Punishment: Why Dictators Join the International Criminal Court." International Studies Quarterly 68(3): sqae087.

- Replication data available on request.

Parente, Francesca. 2023. "Democratic Accountability and Non-Compliance with International Law: Evidence from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights." Online First, Journal of Peace Research.

Hazlett, Chad and Francesca Parente. 2023. "From `Is It Unconfounded?' to 'How Much Confounding Would It Take?' Applying the Sensitivity-Based Approach to Assess Causes of Support for Peace in Colombia." Journal of Politics 85(3): 1145-1150.

Parente, Francesca. 2022. "Settle or Litigate? Consequences of Institutional Design in the Inter-American System of Human Rights Protection." Review of International Organizations 17(1): 39-61.

- Replication data available on request.

Working Papers

All working papers are available upon request.

"From Cautious Optimism to Backlash: Uruguay and the Gelman Decision After Ten Years" (with Debbie Sharnak). Revise and Resubmit.

"The Price of Justice: Compliance with Damages Awarded by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights" (with Jillienne Haglund). Under review.

"Balancing Justice: Damages Awarded by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights" (with Jillienne Haglund). Under review.

"Apples to Apples: How (not) to Compare Compliance Across International Courts."

"Democratic Lock-in and the American Convention on Human Rights" (with Andrew Moravcsik and Cassandra Emmons).

Book Reviews

Parente, Francesca. 2022. "Disability in International Human Rights Law." Law and Politics Book Review 32(3): 32-35.